Metadata

-

Date

-

Last update

-

Tagged

-

Older post

-

Newer post

Love errors

“Error messages are pretty scary, right?”

If you answered with “yes”, I’d like to convince you of the opposite.

Oh, no!

Error messages were something that I did not want to see. They indicated I did something wrong, that my code was bad and I should feel bad.

That was wrong.

Your code is not garbage.

While errors used to exclusively cause a sense of dread and frustration. Now they are often a source of relief, provide an answer to questions, etc.

Don’t get me wrong. They’re still a source of frustration sometimes, and lots of it. Especially when one error is the thing that’s preventing you from making progress.

The most annoying error messages are the ones that don’t tell you anything other than “stuff broke”.

Why thank you Gatsby, that is so incredibly useful pic.twitter.com/uubA2NSdzo

— Emma Bostian (@EmmaBostian) April 7, 2020

Gather information

When you see error messages, READ THEM.

Error messages are an invaluable tool to help you figure out what went wrong. They are not only telling you there is an issue, they are also the first step to fixing that issue!

— Mark Dalgleish (@markdalgleish) August 15, 2019

When I first started programming error messages seemed more scary than helpful. Now sometimes I’m relieved when I have an error message, make a fix and see a brand new error message. https://t.co/Ru2UllFaL6

— Monica.dev (@indigitalcolor) August 27, 2020

Error messages often contain a lot of relevant info. If they don’t tell you exactly what’s wrong or how to fix it. Good ones will at least point you in the right direction.

When presented with an error message, extract as much information as possible from it. Make an effort to understand what it’s telling you.

Again, and again

You will read code more often than you write code. For error messages, this is even more true. (How can something be more true than true? That’s not possible. These questions keep me awake at night.)

Learn by having lots of exposure to errors. That’s how I learn most about programming: by making mistakes, by deliberately breaking things.

Being perfect and following along with tutorials doesn’t expose you to a wide variety of errors. Those hold valuable understanding.

Context

Context is important. The more context you have, the better.

- What language are you using, what framework?

- Which version of that framework?

- Are you on Windows, Mac, Linux, …?

- Which browser are you using?

What did you eat for breakfast?

A lot of that information might not be relevant to the exact problem you’re having. Still, having more information is often better than less.

That’s why a lot of open source projects require you to provide this information when you submit a bug. It might be relevant.

If you know a lot about what you are doing, the source of an error message may be clear to you. Whereas if you dove in without context, the error message might have been indecipherable. This ties into the next tip, keeping the feedback loop short.

Keep the feedback loop short

Try to keep the time between writing code, and discovering an error that code caused as short as possible. The moment right after you write a bug, is the best moment to see the error it caused. It’s the moment where you’ll have the most context.

Luckily, a lot of workflows include tools to provide you with feedback as quickly as possible.

In web development, that might take the form of an automatically reloading web browser, showing you the results of the code you wrote.

It might be powered by browsersync, or a fancy setup using React Native fast refresh.

What matters is the code you just wrote is getting executed and you will be presented with any errors it may cause quickly.

Scroll up

When faced with multiple errors, the top one will usually provide you with the most relevant information.

If one thing is broken, that might cause other things to break (and show errors). Fixing the original problem will then also solve the other errors.

Ofcourse this isn’t always the case. Even if it’s not, tackling errors one at a time, starting with the oldest one is useful.

When you try to fix a lot of things at once, it becomes next to impossible to predict which impact a specific change had. Did it fix it, or did you create a whole new problem?

Tackling one error at a time, and making small changes, can prevent that issue. While keeping the feedback loop short.

Reading an error

Consider the following, highly sophisticated piece of code. I’ll use a JavaScript file, executed locally with node.js

const corgi = { cute: true, bark() { console.log("woof"); },};

function squirrel() { console.log("The corgi sees the squirrel"); corgi.actions.bork();}

function walk() { console.log("Taking a walk, when suddenly, a squirrel appears!"); squirrel();}

walk();It has an error, and while it might be easy to spot in this case. I’ll read the error message to figure out what happened.

The following error appeared when I tried executing this code:

/home/nicky/error-testing.js:10 corgi.actions.bork() ^

TypeError: Cannot read property 'bork' of undefined at squirrel (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:10:19) at walk (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:15:5) at Object.<anonymous> (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:18:1) at Module._compile (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:774:30) at Object.Module._extensions..js (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:785:10) at Module.load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:641:32) at Function.Module._load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:556:12) at Function.Module.runMain (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:837:10) at internal/main/run_main_module.js:17:11Dissecting the error

The first line tells me 2 things. It happened in the error-testing.js file that’s in the home folder on my computer.

This is true! I already knew this, because I just made that file and I have that piece of information as context.

The :10 tells me this error happened on line number 10.

It shows the piece of code that triggered the error beneath it.

A caret (^) is pointing at the exact location the error was triggered.

TypeError: Cannot read property 'bork' of undefined tells me which kind of error this is. In this case, a TypeError.

Followed by the error message.

The next part is the stacktrace.

For me personally. This is what gave errors the scarefactor that made me say: “I can’t understand this, better not read it”. They’re big, unwieldy, and if you don’t know which information they convey, quite indecipherable.

at squirrel (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:10:19)at walk (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:15:5)at Object.<anonymous> (/home/nicky/error-testing.js:18:1)at Module._compile (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:774:30)at Object.Module._extensions..js (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:785:10)at Module.load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:641:32)at Function.Module._load (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:556:12)at Function.Module.runMain (internal/modules/cjs/loader.js:837:10)at internal/main/run_main_module.js:17:11The stacktrace holds a bunch of information about how your program came across the error. It shows different steps in the code that eventually led to the error. Each line tracks the error one step backwards, following a chain of function calls, all the way up until the step where I ran the program with node.js.

The first line tells us that the error was found at /home/nicky/error-testing.js.

The :10:19 makes it even more specific. The error happened at line 10, column 19. In other words on the 10th line, at the 19th character.

Note this is exactly the same place as indicated by the caret (^) previously.

The next lines are structured identically, each tracing the error back a step.

It traces the error all the way back from the squirrel function, to the walk function, and even to the internal code that was used to make this program run.

I’m not going to pretend like I know what’s going on in most of those lines, because I don’t.

When using frameworks, it is common for stacktraces to filled with lines from deep within that framework.

Most of the time, it’s fine to ignore those and look for the entries that mention code you wrote.

When you need information about the lines from the framework, you’ll know.

Fixing the error

So the message was Cannot read property 'bork' of undefined.

Ok, the location pointed me to corgi.actions.bork()

The message means corgi.actions is undefined.

Upon checking, there is no such thing as actions on the corgi object (and thus, it’s undefined).

I changed corgi.actions.bork() to corgi.bork() and ran the code again.

Oh, no! Error again! Another one though. Progress!

This time the error message reads corgi.bork is not a function.

Silly me, I made a typo.

There is no bork on the corgi object, that’s why it’s undefined! No borking corgis here!

Another change to corgi.bark(), no errors, 🎉.

Google for errors

The error messages alone won’t always be enough to figure out what is going on. Time to consult the biggest repository of knowledge there is, the internet.

Swyx shared some of his knowledge and wrote about how to search for your errors.

TypeScript

Typescript has an incredibly high spooky-factor 👻. I avoided seriously trying it for a long time because I was scared. When I tried it out, it bombarded me with cryptic errors I couldn’t understand, and I ran away. When I tried it again, the same thing happened. This cycle repeated a few times.

The language continued growing in popularity and it kept getting better. One of the big bullet points for a major version release was “better error experience”.

🎉 TypeScript 3.0 is here!!!! 🎉

— TypeScript (@typescript) July 30, 2018

Check out project references, extractable parameter lists, easier errors, and more! https://t.co/CtNIvumwLl pic.twitter.com/Da2CbPE9xn

I tried again, and this time I stuck with it and made effort to understand what errors meant.

I still thought many TypeScript errors were terrible. Not because of their content, but because of how they are formatted when you see them.

I really liked the promise that you’ll see more errors during development, before you even run your code, and less during runtime.

.@TypeScript is awesome

— swyx (@swyx) March 7, 2020

I was copying and pasting some JS tutorial code that I didnt know was broken. TS immediately caught it and told me what was wrong. Fixed it without having to run the code. Who needs dev servers when you can have language servers?#ThankYouTypeScript pic.twitter.com/t52VnxuRoz

Examples

React

React has some really helpful errors.

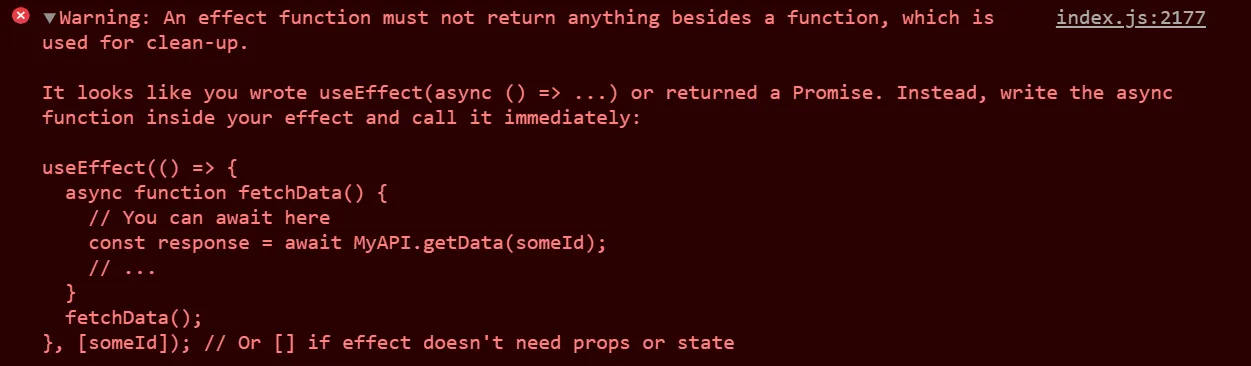

If you try to pass an asynchronous function to useEffect, a helpful error message will tell you exactly what’s wrong and even tell you how to achieve what you are trying to do.

Another example is an error that appears when trying to use a ref.

That big fat error is really helpful:

Warning: Function components cannot be given refs. Attempts to access this ref will fail. Did you mean to use React.forwardRef()?

A pseudo-element

While working on my blog, specifically on the block quotes, the following error messages popped up:

This time, the first line did not immediately point me to the correct location.

The stacktrace, tracing the error back, says the fauly code passed by commons.js at line 90414.

That can’t be right. I don’t have any file that long.

That incredibly long file is not the code I wrote, but the result of it that runs in the browser. Source maps are often used for this reason. They translate the locations in that resulting file back to the original source, to the files you wrote.

Luckily, the stacktrace also mentioned BlockQuote.

footer: { fontSize: 1, fontWeight: "bold", fontStyle: "normal", "::before": { // make sure mdash is on same line as footer float: "left", content: "'\\02014\\000A0' ", },},Oopsie, a space where there shouldn’t be one!

Removing that extra space at the end of the value for content made the pages using this code render again!

Styling

Working on my blog again, I was presented with these error messages:

At first sight, those messages were quite the unhelpful. I’m styling lots of things on my site in the same way, and this is wrong. Why?

The error pointed me this this piece of code: an <ul> tag styled with theme-ui.

<ul sx={{ display: `grid`, gridTemplateColumns: `1fr`, gridGap: 4, marginBottom: 3, listStyle: `none`, padding: 0, }}>The problem ended up being the gridGap.

It turns out that gridGap was not a valid option for the sx-object (aka. the SystemStyleObject the error mentioned), but gap was.

After changing the gridGap to gap, all was well again.

Bonus: make errors better

While teaching about compound components, Kent C. Dodds shared an incredibly useful tip.

He made a lot future errors easier to understand by throwing an error in the code he wrote.

As a result, a very helpful error message will be shown if the component he wrote is used incorrectly. If he didn’t do this, the resulting error message would be very cryptic and probably cause a lot of frustration for anyone that came across it.

React context/hooks tip: Create a custom hook for React contexts that shows a helpful error.

— Nicky (@NMeuleman) February 14, 2020

Learned by watching @kentcdodds

❌ Case 1: Using the TeamPickerContext directly leads to a cryptic error.

✅ Case 2: Using the useTeamPickerContext hook shows a helpful error. pic.twitter.com/nNNPp9zmdO

In a different post Kent explained how to make Jest testing errors more useful by manipulating the stacktrace.