Metadata

-

Date

-

Last update

-

Tagged

-

Older post

-

Newer post

On accounts and passwords

Accounts. We all have them, the amount of accounts a single person controls varies wildly.

A quick internet search revealed that the average user had over 90 accounts. In 2015! How accurate that number is, no idea. The point is, it’s a lot.

By far the most popular method to secure an account is with a password.

Passwords

Because passwords are so popular to secure accounts, nefarious individuals have made it their mission to find out your secret passwords. And so begins an eternal armsrace.

Many methods of discovering/cracking passwords exist.

If a password is too short, that means it’s vulnerable to a brute force attack.

If it’s a common word or sentence, that means it’s vulnerable to a dictionary attack.

To oversimplify, making a password more secure means making attacks against them take an unreasonably long time. Note: That statement has about a million caveats.

Picking a better password

Passwords in general are not a rigidly secure way to authenticate.

As a broad statement, if your password is around 7-8 characters, it is not long enough.

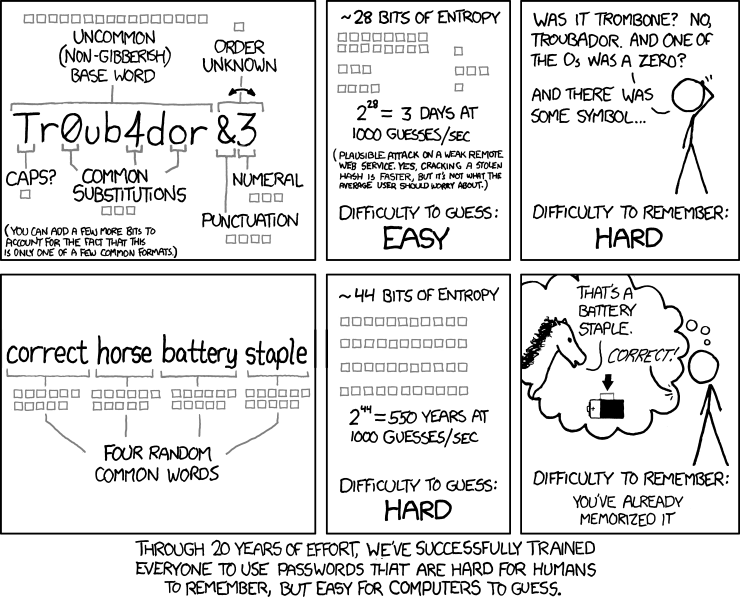

A long and complicated one is hard to remember. Making it easier to remember will often reduce the security of the password. As a result, a lot of passwords are hard for a human to remember, and easy for a computer to crack.

An XKCD comic mentions this problem and proposes a method that keeps the security of longer, complicated passwords while making them easier to remember.

The example proposed using correcthorsebatterystaple as password.

- This is long enough not to be vulnerable to a brute force attack. (for now)

- It’s not going to be extremely vulnerable to a dictionary attack, because the words are random and seemingly have no relation.

A manager

We previously discussed making a single password more secure.

That’s fine, but you should never reuse passwords. That means the amount of passwords you have to remember increases with the amount of accounts you have. Unsustainable. Even if you manage to remember them all, they’re probably less complicated and secure than if you remembered a single one.

The solution? Not remembering a lot of passwords, but one really good one.

In other words: use a password manager.

A password manager acts like a vault that holds the info to a bunch of login names and the associated passwords. Basically, it’s a fancy, secure database. If it’s programmed correctly that is.

One of the popular methods to gain access to a vault is with a “master password”.

That master password should be really good. Oversimplified reason: the encryption that’s used to protect your vault is derived from that master password.

Nearly all password managers come with a way to randomly generate a password that will be way more complex than one you could reasonably remember. All my passwords are 25 (or 30, 🤷♂️) characters long. They’re random and I have no clue what they are.

When a website requires registration, I don’t reuse passwords to sign up. I add an entry in my password manager and use that instead.

-

If I never use that website again, it doesn’t matter.

It means your password manager vault is now a single entry bigger, which is not a big deal.

-

If that website is shady or gets compromised and your password leaks onto the internet.

It doesn’t also compromise your other accounts because the password is random and will be unique to that website.

Here’s a video where Mike Pound from Nottingham University explains more about how password managers work.

Have i been pwned?

- Did my password get leaked?

- Did a company have a data breach and is my password now compromised?

Or, a way to say it that’s at least twice as entertaining: Have I been pwned?

The website haveibeenpwned.com tries to answer that question.

Whenever there’s a big breach or leak of account details, this website will try to keep track of it.

The person who runs this website, Troy Hunt has built numerous useful tools that use that data.

You can enter the email address you often use for accounts to check if it’s been pwned. If that address appears in a security breach, the site will tell you in which ones. Each result will include some information about the breach like the approximate date it happened, and which data was compromised.

Another tool he built will tell you if a password has been cracked.

The end result is: the site tells you if the password you typed in was found in a list of compromised passwords.

It will do that check without ever receiving the password. Whaaaaat 🤯.

It uses a k-anonymity model to allow a password to be searched by a partial hash.

- You first hash your password and send the API a part of that hash.

- It then sends back a bunch of potential matches (the hashes that start with the same characters you provided), each with the amount of times that hash was found in a database full of cracked passwords.

- You look at the list of hashes that came back and see if there is an exact match to the hash of your password.

Multi Factor Authentication

The gold standard for checking your identity is multi factor authentication.

It require the presentation of 2 or more different factors of identification.

- Something you know (eg. a password)

- Something you are (eg. a fingerprint)

- Something you have (eg. a physical key)

2 different factors are way more secure than a single one, or multiple instances of a single one (like having 2 passwords is not multi factor.)

Combining at least 2 of those factors make it much harder for an attacker to succesfully gain access to what you’re protecting.

A common example of this is withdrawing money at a bank. Your banking card is the thing you have and the PIN is the thing you know.

Let’s assume I had an account at SuperSecret™️, and it was protected by 2 factors. A password as the something I know, and a device generating codes as the something I have.

If someone guessed my password and tried to log in to my SuperSecret™️ account. They (hopefully) don’t have access to the device I use to provide the second factor, and would be left unable to login to my SuperSecret™️ account.

At the same time, I would probably be notified of an unsuccessful login attempt, which would cause me to change that password.

Not everything

Increased security usually comes at the cost of decreased convenience (like making a passord more complicated, but harder to remember). That’s also the case with multi factor authentication and causes a lot of people to shy away from it.

The ideal is having the benefits of the increased security it offers, while minimizing the extra hassle.

That’s why that little “remember this device” checkbox appears on many sites asking for a second factor (often the “something you have” in the form of a one-time-password) Or why many sites don’t ask you to verify your identity constantly, but when you want to change sensitive information (eg. payment details) the site asks for that second factor again.

Losing the “something you have” factor can be quite the issue. Not being able to provide that can cause you to be locked out of your accounts.

Another reason not to use it, is because some services flat out don’t support it. Luckily the list of services that don’t is getting smaller and smaller as time goes on. In 2020, the vast majority of large services support 2FA.

One time passwords

The most popular method to provide the “something you have” factor is through smartphone apps that generate a one time password.

While the exact method of how this works is fascinating, the enduser shouldn’t care about how the cookie is made, only that it’s delicious. They have a smartphone that generates codes, those codes (that change) are the thing they need to provide when asked for their second factor.

Ok, what happens is too interesting not to share. Here’s a brief, oversimplified explanation of what happens for a time based one time password in Google Authenticator (and many other apps).

The phone knows a long secret code that was shared with them when the account was set up in the app. This is commonly done by letting you scan a QR code. That secret code is combined with the current time, math happens, and a resulting code (TOTP) is displayed.

The server asking for verification also knows that initial secret code and does the same thing. If the resulting codes match, voila, sesame opens.

When that physical device is the only object that holds the secret sauce to your OTPs, and happens to be your phone, even upgrading to a new phone will leave you scratching your head. Phones also get lost, they get broken, spontaneously stop working, …

The Google Authenticator app now supports import/export of accounts. Making switching to a new phone way more convenient than it used to be. (You used to have to delete all accounts on one phone and add them again on another phone.)

Another application that generates TOTPs, Authy, also stores that long secret code in the cloud, so you can access it when you need to.

Sign in with …

A lot of accounts provide the option to sign in through another online service. (eg Google, Facebook, Twitter, GitHub). Soon, Apple is joining the party.

They reduce the hassle of having to sign up for yet another account by using the authorization for an account you already have, theirs.

Many of them use a the OAuth process under the hood.

The site offering this ask the provider (eg. Google) for some information about you (eg. email and name). If the user allows this and logs into the provider, OAuth sends the site a token confirming you’ve signed in.

Apple

A new addition is “sign in with Apple”. It uses Apple’s method of identity confirmation, that also means it works with their face detection (Face ID) and fingerprint detection (Touch ID).

One of the big plusses users will have is the ability to hide their email address when signing up to a service. Apple will then provide the site asking for your email with an anonimised one, and forward mails sent to it to your real email.

This makes it harder for shady sites to sell your email address and spam you.

Sign in with Apple won’t track or profile you as you use your favorite apps and websites, and Apple retains only the information that’s needed to make sure you can sign in and manage your account.

Opinions and what I use

As password manager I use KeePassXC.

I use 2FA on many sites and store the TOTPs in Google Authenticator.

If you are not a fan of using 2FA (eg. because of the extra hassle). Please use it for your email.

Your email often serves as a sort of master account with the ability to reset passwords for a bunch of other accounts.

On the topic of 2FA, I avoid the SMS kind. SMS is not as secure and has resulted in a bunch of high profile accounts getting hacked. Often through some form of social engineering.

Social logins, I’m not really a fan of them. While the security mechanism of these big companies is almost certainly far superior to that of a random website I’m signing up for. I don’t like these big companies knowing when I sign into anything. Especially if said company’s business model depends on selling advertisements and they have a vested interest in targeting advertisements as well as they can.

I also prefer not using them because I never seem to remember which one I used where. Having every account live as an entry in my password manager simplifies this.

As for “log in with Google”. I avoid that because my trust in the longevity of anything coming out of that company is not high. They famously retire many of their services, even if said service is universally beloved and has been around for years. Notable examples of their services that went the way of the dodo are:

- Google Reader

- Google Inbox

- Picasa

Soon Google Hangouts will join that list. Picasa was 13 years old when they pulled the plug. 13! That one still stings.

Facebook, I avoid because… They have a less than sterling trackrecord when it comes to privacy.

The “login with Apple” thing would be cool, I hope it becomes widespread and isn’t only available on their appstore and their own products.

Apple is going to force developers on iOS providing other single sign on services to also implement theirs.

Oh, Apple.